Grandparent and Third-Party Visitation Rights in Connecticut (C.G.S. 46b-59)

Grandparent and Third-Party Visitation Rights in Connecticut (C.G.S. § 46b-59)

Need help with your divorce? We can help you untangle everything.

Get Started Today

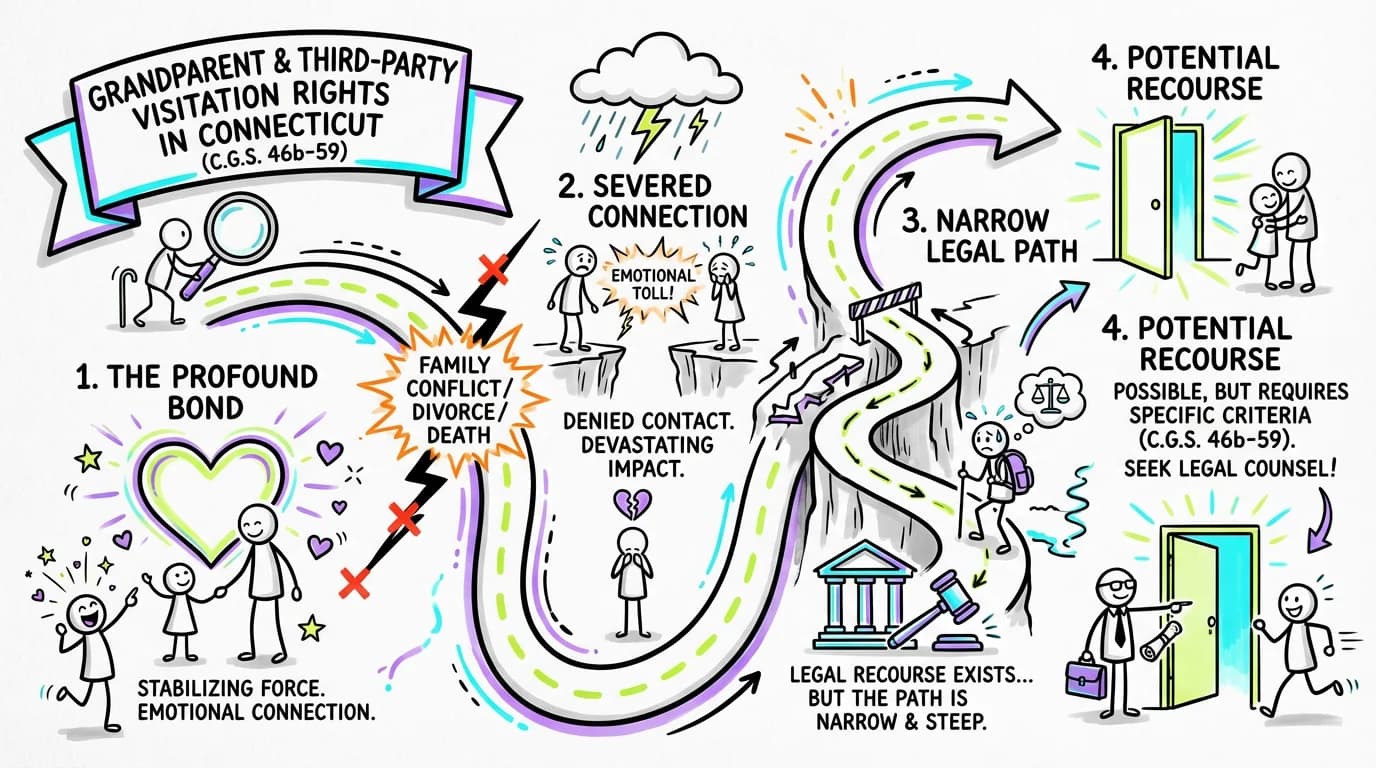

The bond between a child and a grandparent, stepparent, or other caring adult can be one of the most profound and stabilizing forces in their life. When divorce, death, or family conflict threatens to sever that connection, the emotional toll can be devastating for both the child and the adult. If you are a non-parent in Connecticut being denied contact with a child you love and have helped raise, you may be wondering if you have any legal recourse. The answer is yes, but the path is narrow, steep, and legally demanding.

In Connecticut, the law begins with a powerful constitutional principle: fit parents have the fundamental right to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children. This includes the right to decide who their children see and associate with. Courts are extremely reluctant to interfere with this right.

However, the Connecticut General Assembly created a specific, limited exception under Connecticut General Statutes § 46b-59. This statute provides the sole legal pathway for a third party, such as a grandparent, to petition the court for visitation rights.

This article will provide a comprehensive guide to understanding your rights and the significant legal hurdles you must overcome. We will break down the challenging two-part test at the heart of C.G.S. § 46b-59, explaining what it means to establish a "parent-like relationship" and how to prove that denying visitation would cause "real and significant harm" to the child. Understanding this high legal standard is the first and most critical step in this difficult journey.

The Constitutional Hurdle: Why Third-Party Visitation is So Difficult

Before diving into the specifics of the Connecticut statute, it's essential to understand the legal landscape that shapes it. The foundation for third-party visitation law across the country was established by the U.S. Supreme Court case Troxel v. Granville (2000).

In Troxel, the Supreme Court affirmed that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects a parent's fundamental right to rear their children. The court found that "fit parents are presumed to act in the best interests of their children." This means that as long as a parent is deemed "fit" (i.e., not abusive or neglectful), the court must give "special weight" to their decisions—including the decision to limit or deny visitation with a grandparent.

Connecticut courts have fully integrated this principle. They will not simply substitute their own judgment for a parent's. A judge cannot grant visitation just because they think it would be "nice" for the child or in their "best interest" in a general sense. The "best interest of the child" standard, which is the guiding principle in custody disputes between parents, does not apply here in the same way.

Instead, a third party seeking visitation must overcome the constitutional presumption in favor of the parent. C.G.S. § 46b-59 was carefully written to comply with this constitutional requirement, which is why it sets such a high bar for anyone petitioning the court.

Understanding C.G.S. § 46b-59: The Two-Part Test for Visitation

Connecticut General Statutes § 46b-59 lays out a strict, sequential, two-part test that any non-parent must pass to be granted visitation rights. You must successfully prove both parts. If you fail on the first part, the court will dismiss your case without ever considering the second.

- The Standing Test: The petitioner (the person seeking visitation) must first prove to the court that they have a "parent-like relationship" with the child. This is a threshold issue; it determines whether you even have the right to ask the court for visitation.

- The Merits Test: If, and only if, the court finds a parent-like relationship exists, the petitioner must then prove that denial of visitation would cause real and significant harm to the child.

Let's break down each of these demanding requirements in detail.

Part 1: Proving a "Parent-Like Relationship"

The first gate you must pass through is proving "standing"—your legal right to bring the case. Under C.G.S. § 46b-59, this means demonstrating that your connection with the child goes far beyond that of a typical loving relative or family friend. You must show that you have, in effect, functioned as a parent to the child.

What is a "Parent-Like Relationship"?

The statute itself doesn't provide a single, neat definition. Instead, it requires the petitioner to allege and prove facts that are "similar to that of a parent." The court will look for evidence that the petitioner took on significant parental responsibilities and formed a bond with the child that is parental in nature.

The key is demonstrating that you have shouldered the duties of parenthood, not just enjoyed its pleasures. The court will consider factors such as:

- Did the child reside with you? Living in the same household for a significant and continuous period is one of the strongest indicators of a parent-like relationship.

- Did you provide for the child's daily needs? This includes providing food, shelter, clothing, and financial support.

- Did you provide for the child's care, discipline, and nurturing? This involves the day-to-day work of parenting: helping with homework, enforcing rules, providing emotional support, taking them to doctor's appointments, attending parent-teacher conferences, and making decisions about their welfare.

- Did you establish a bond that is central to the child's well-being and development? The court looks for a deep, formative attachment where the child relies on you for guidance, comfort, and stability in a way they would a parent.

Gathering Evidence to Prove the Relationship

To convince a judge, you need more than just your own heartfelt words. You must present concrete, verifiable evidence. Think like a lawyer and start documenting everything that supports your claim.

- Testimony: Your own detailed testimony is crucial. Be prepared to describe specific routines, responsibilities, and interactions. Testimony from others—such as teachers, neighbors, coaches, or family friends who witnessed your parental role—can be very powerful.

- Documents:

- School Records: Were you listed as an emergency contact or authorized to pick up the child from school?

- Medical Records: Did you take the child to doctor or dentist appointments? Are you listed on any intake forms?

- Financial Records: Can you produce receipts or bank statements showing you paid for groceries, clothes, school supplies, summer camp, or medical co-pays?

- Photographs and Videos: While photos from holidays and birthdays are nice, images showing the mundane reality of your parental role are more compelling. Look for photos of you cooking dinner with the child, helping with a school project, or reading a bedtime story.

- Communications: Emails, text messages, or letters between you and the legal parents that discuss the child's care, schedule, or well-being can demonstrate your integral role in the child's life.

Common Scenarios: Where the "Parent-Like" Test Succeeds and Fails

Understanding the difference between a loving relationship and a legally recognized "parent-like" one is critical.

- Scenario 1 (Likely to Succeed): A maternal grandmother moves in with her daughter and grandson after the father leaves. For four years, while the mother works two jobs, the grandmother is the primary caregiver. She gets the child ready for school, packs his lunch, picks him up, helps with homework, takes him to all his appointments, and handles discipline. Here, the grandmother has clearly assumed a parental role.

- Scenario 2 (Likely to Fail): A devoted grandfather sees his grandchildren every weekend. He takes them to the park, buys them toys, and hosts family dinners. He loves them dearly, and they love him. However, he does not live with them, provide for their daily financial needs, or make decisions about their education or healthcare. While this is a wonderful and important relationship, a court would likely find that it does not rise to the level of "parent-like" as defined by C.G.S. § 46b-59.

If you cannot meet this first test, your petition will be dismissed. If you can, you have earned the right to proceed to the second, even more difficult, part of the test.

Part 2: Proving "Real and Significant Harm"

Once a parent-like relationship has been established, the legal focus shifts to the child. The petitioner now bears the heavy burden of proving that denying visitation would cause "real and significant harm" to the child.

This is the highest and most difficult standard to meet in Connecticut family law.

The Highest Bar: What Constitutes "Real and Significant Harm"?

This standard is intentionally vague and extremely high. It requires much more than showing the child will be sad, upset, or will miss you. The emotional pain of a child being separated from a loved one, while real, is often not enough to meet this legal definition.

"Real and significant harm" implies a severe and demonstrable negative impact on the child's psychological, emotional, or physical well-being. The harm must be observable and substantial. While there is no exact formula, courts have interpreted this to mean a level of harm that could jeopardize the child's healthy development.

Think of it this way: the harm must be so significant that it outweighs a fit parent's constitutional right to raise their child as they see fit. This is why evidence is so critical. You cannot simply argue that the parent is being unreasonable or that you would be a "better" influence. The entire case hinges on the provable, negative impact on the child.

Evidence Needed to Demonstrate Harm

Because this standard is so high, your personal testimony is rarely sufficient. Proving real and significant harm almost always requires the use of expert witnesses.

- Child Psychologists or Therapists: This is often the most crucial evidence. A qualified mental health professional can evaluate the child, assess the nature of their bond with you, and provide expert testimony to the court. They can identify specific, diagnosable harm, such as the onset of clinical anxiety, depression, behavioral regression (e.g., bedwetting), or other trauma responses directly linked to the cessation of contact.

- Guardian Ad Litem (GAL) or Attorney for the Minor Child (AMC): In highly contested cases, the court may appoint a GAL or an AMC. This is a specially trained attorney who represents the child's best interests. They will conduct an independent investigation—interviewing the child, parents, petitioner, teachers, and therapists—and then make a recommendation to the court about the potential for harm. Their report carries significant weight with the judge.

- Teachers and School Counselors: These professionals can provide objective testimony about changes in the child's behavior, academic performance, or social interactions at school that coincided with the loss of contact with you. A sudden drop in grades or withdrawal from friends can be powerful evidence of harm.

Real-World Example of Proving Harm

Imagine a 7-year-old child who lived with her stepfather from age 2 to 6. Her mother and stepfather divorce, and the mother, who has sole custody, cuts off all contact between the child and her former stepfather, to whom the child is deeply bonded and calls "Dad."

- Parent-Like Relationship: The stepfather can likely prove this. He lived with the child, provided daily care, and was her primary father figure for most of her life.

- Real and Significant Harm: After the contact stopped, the child began having severe nightmares, her grades plummeted from A's to C's, and her teacher reported that she became withdrawn and frequently cried in class. The mother refused to take her to therapy. The stepfather hires an attorney who petitions the court. The court appoints a GAL. The GAL interviews the child, teacher, and stepfather. A child psychologist retained by the stepfather evaluates the child and testifies that she is showing symptoms of Adjustment Disorder with Depressed Mood and that the abrupt loss of her primary attachment figure (the stepfather) is the direct cause. The GAL's report concurs.

In this scenario, the stepfather has presented strong evidence of "real and significant harm," giving him a fighting chance of being granted a court-ordered visitation schedule.

The Court Process: Filing a Petition for Visitation

Initiating a C.G.S. § 46b-59 action is not a simple matter of filling out a form. It is a formal lawsuit that requires strict adherence to legal procedure.

- Step 1: Draft and File the Petition: You must file a "Verified Petition for Visitation" with the Connecticut Superior Court. "Verified" means you are swearing under oath that the facts alleged in the document are true. The petition must clearly and specifically state the facts that support both prongs of the test: the nature of your parent-like relationship and the reasons you believe the child will suffer real and significant harm if visitation is denied.

- Step 2: Serve the Parents: The child's legal parents are the respondents in the lawsuit. They must be officially notified of the case through a process called "service of process." This involves hiring a state marshal to personally deliver a copy of the lawsuit paperwork to each parent.

- Step 3: The Evidentiary Hearing: The court will schedule a hearing. This is not an informal discussion; it is a mini-trial. Both sides will have the opportunity to present evidence, submit documents, call witnesses to the stand, and cross-examine the other side's witnesses. As the petitioner, the burden of proof is entirely on you.

- Step 4: The Court's Decision: After hearing all the evidence, the judge will make a decision.

- If the judge finds you have not proven a parent-like relationship, the case is dismissed.

- If the judge finds you have proven a parent-like relationship but have not proven real and significant harm, the case is dismissed.

- Only if the judge finds you have proven both elements by a "preponderance of the evidence" (meaning it is more likely than not) will the court grant visitation. The court will then issue a specific order detailing the frequency, duration, and conditions of the visitation.

Common Mistakes and Pitfalls to Avoid

Navigating a C.G.S. § 46b-59 petition is fraught with potential errors. Being aware of them can save you time, money, and heartache.

- Mistake 1: Underestimating the Burden of Proof. The most common mistake is believing that your love for the child and the child's love for you is enough. It is not. You must approach this with a clear understanding of the high legal standards and the need for objective evidence.

- Mistake 2: Focusing on the Parents' Flaws. While it may be tempting to list all the reasons you believe the parent is making a poor decision, the case is not about them. It is about your relationship with the child and the harm to the child. Attacking the parent's character can make you appear hostile and can easily backfire, making a judge less sympathetic to your cause.

- Mistake 3: Waiting Too Long. The passage of time can weaken your case. If a parent-like relationship existed but you have had no contact for two years, it becomes much harder to argue that the bond is still central to the child's life and that its absence is causing current harm.

- Mistake 4: Trying to Do It Yourself. This is one of the most complex and nuanced areas of Connecticut family law. The procedural rules are strict, the evidentiary standards are high, and the constitutional issues are significant. Attempting to file a C.G.S. § 46b-59 petition without an experienced family law attorney is almost certain to fail.

Summary and Key Takeaways

Seeking court-ordered visitation as a non-parent in Connecticut is an uphill battle, but it is not impossible for those with the right facts on their side.

Remember these key points:

- Parental Rights are Paramount: Connecticut law is designed to protect the constitutional right of fit parents to raise their children.

- C.G.S. § 46b-59 is Your Only Path: This statute provides the exclusive, narrow legal avenue for seeking visitation.

- The Two-Part Test is Absolute: You must first prove a "parent-like relationship" and then prove that denying visitation would cause "real and significant harm" to the child.

- Evidence is Everything: Success depends on your ability to present concrete, objective evidence—often including expert testimony—to support both parts of the test.

- This is a Formal Lawsuit: The process is complex, adversarial, and requires skilled legal navigation.

Legal Citations

- • C.G.S. § 46b-59 (Visitation Rights) View Source